-

30 January

1840

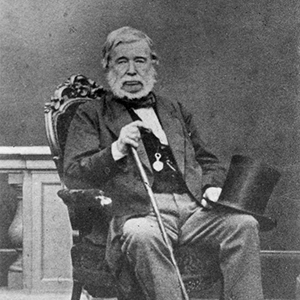

Lieutenant Governor William Hobson arrives in the Bay of Islands and proclaims that no existing land titles in New Zealand would be recognized as valid unless confirmed by the British Government.

Lieutenant Governor William Hobson -

1 February

1840

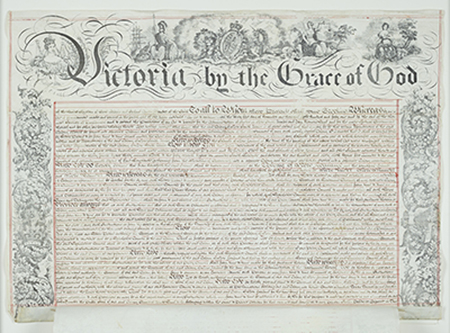

Hobson begins to draft the Treaty of Waitangi based on instructions from Lord Normanby and texts he had seen in Sydney.

-

2 February

1840

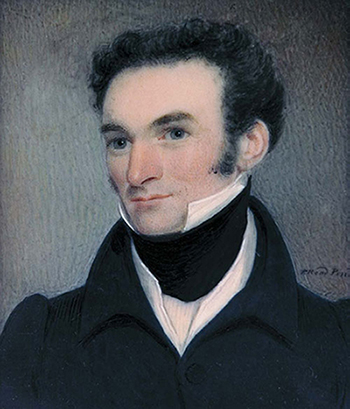

Hobson suffers a stroke and is paralysed. British Resident James Busby takes over treaty drafting.

James Busby -

3 February

1840

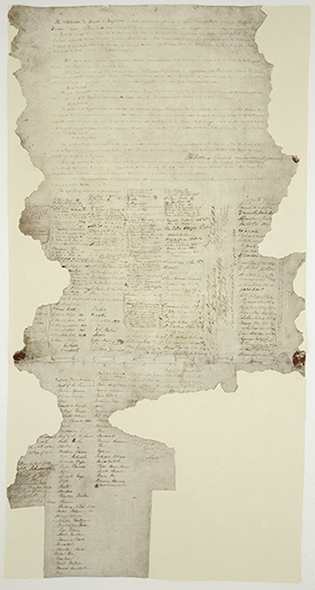

Busby creates a treaty draft dated February 3. This draft has the phrases “lands and estates forests fisheries” and “right of pre-emption”.

-

4 February

1840

Busby creates a treaty draft dated February 4 that has no reference to “lands and estates forests fisheries” and “right of pre-emption”. Reverend Henry Williams and his son Edward translate the final draft into the Maori language. The Tiriti o Waitangi was the only Treaty authorised by Hobson to be signed by the chiefs.

Reverend Henry Williams -

5 February

1840

Hobson reads the treaty in English and Williams reads the Treaty in Maori to the gathering of 2000 people. The chiefs discuss it with Hobson for five hours then well into the night with the missionaries and decide it is to their advantage to sign the Tiriti the next morning.